Damion Jones, 31, was at work when he felt the pain in his stomach. He knew that something wasn’t right, but neither he nor his employer’s onsite clinic could pinpoint what was wrong. Next came shortness of breath. “I couldn’t walk up the hill at work without getting winded,” Jones said. “And I couldn’t get rid of my cough.”

So began the odyssey that eventually brought Jones to UAB’s Comprehensive Transplant Institute (CTI). When Jones went to his doctor, he was told that his gallbladder was the culprit. But after gallbladder surgery, Jones didn’t bounce back. He was still plagued by a cough and just didn’t feel like himself. On a Sunday morning in early 2023, Jones awoke coughing up blood. He and his wife, Shemika, headed to their regional hospital, where doctors found multiple blood clots in his lungs and identified the underlying cause: heart failure. An ambulance brought Jones to UAB’s doorstep.

José Tallaj, M.D., a cardiologist with the UAB CTI, said that Jones’ winding journey to UAB is understandable, given the rarity of heart failure at his age. “As young, active patients get sick, they may not know that they’re developing heart failure,” Dr. Tallaj said. “By the time they come to us, they are very ill.”

A ticking clock

When Jones arrived at the UAB CTI, he was in cardiogenic shock, a rare and life-threatening condition in which the heart can’t pump enough blood to sustain the brain and the body’s organs. “He was in truly bad shape,” Dr. Tallaj said.

Jones put it more bluntly. “Not only did I have heart failure, but my kidneys and liver were shutting down,” he said. “It was like my heart was saying, ‘I’m just going to supply blood to major organs; smaller organs can take the hit.’”

Dr. Tallaj and his team found that medications to support Jones’ blood pressure weren’t enough. “We placed an intra-aortic balloon pump in his heart through his groin to help him survive the cardiogenic shock,” he said. “But we had to wait for his kidneys and liver to get better in order to perform the transplant.”

Although Jones was cleared for and placed on the transplant waiting list, his condition was dire. “When someone is as sick as Mr. Jones was, there are a few things we discuss,” said Dr. Tallaj. One is a surgically implanted durable mechanical device called an LVAD that pumps blood from one chamber of the heart to the rest of the body. The other is ECMO, an external and temporary heart-lung machine that takes over blood circulation. Both alternatives are designed to help patients with end-stage heart failure.

Due to the scarcity of donor organs, heart transplantation is relatively rare. A patient’s spot on the waiting list is determined by several factors, including how sick they are, their blood type, and their body size. According to Dr. Tallaj, the waiting time for those with an LVAD can be months to years, while patients who have balloon pumps or who are on ECMO may get an organ in days or weeks. The clock was ticking for Jones. “My heart was functioning at 5%, so we decided that I’d stay on the list for few weeks,” he said. “If I didn’t receive a heart by then, then I’d have to go with the LVAD until a heart became available.”

But Jones didn’t give up hope, attributing his calmness throughout his journey to God’s guidance. “I’m a spiritual person and I had time to talk to Him and meditate,” he said. “I never got scared and knew that whatever happened was meant to happen.”

The beat goes on

Jones’ equanimity was rewarded on Feb. 20, 2023, when he received his new heart. Over the course of two weeks in the hospital and six weeks of living close to UAB for twice weekly monitoring, he had just one minor rejection scare. “One of the complications of transplant is that the body will try to reject the new heart,” explained Dr. Tallaj. “Mr. Jones’ rejection episode was resolved by increasing oral steroids for a few days.”

Jones’ medication regimen is designed to prevent rejection. “I take 60 pills a day – 34 in the morning, 8 in the evening, and 24 before bed,” he said. Dr. Tallaj noted that, one year following transplant, patients typically discontinue some of their preventative medications. “The chance of rejection decreases down with time, allowing us to reduce the dose of anti-rejection medications” he said.

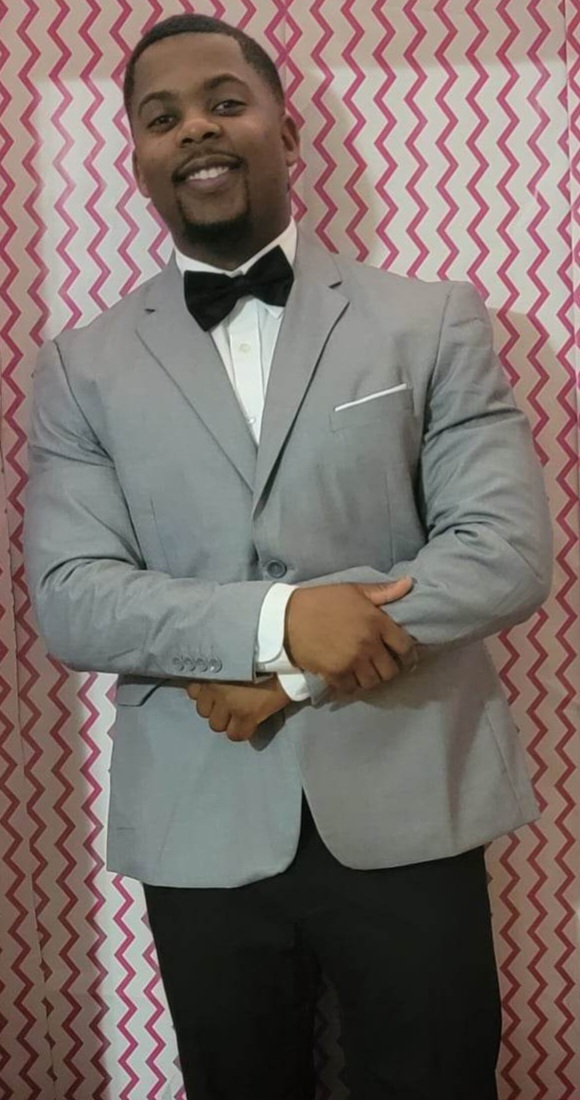

Now back at home in Fort Payne, Ala., Jones is thriving. Five months post-surgery, he returned to work and was back at the gym doing cardio workouts. He has strong motivation to do what it takes to resume his life: in addition to spending time with his four-year-old son, Jaxson, he and Shemika recently welcomed the arrival of Jayden.

Gratitude abounds

Jones is looking forward to the one-year anniversary of his transplant, when he will have the opportunity to reach out to his donor’s family. “I hope I can meet their family to give thanks and show my gratitude,” he said.

Dr. Tallaj also cherishes donor families, saying that the UAB CTI values and honors what they do for patients. “Donor families are heroic,” he said. “In the midst of significant tragedy, they are willing to help strangers.”